Human capital strategy in AEC era: free flow or controlled trickle?

“The Era of AEC (ASEAN Economic Community)”

Management Thinking Series

-Human capital strategy in AEC era: free flow or controlled trickle?-

This series studies the AEC (ASEAN Economic Community) that is formed at the end of 2015.

In this report, we will study the key points and challenges in the ASEAN labor market and investigate national policies in each country concerning free flow of skilled labor and the impact on businesses.

Summary

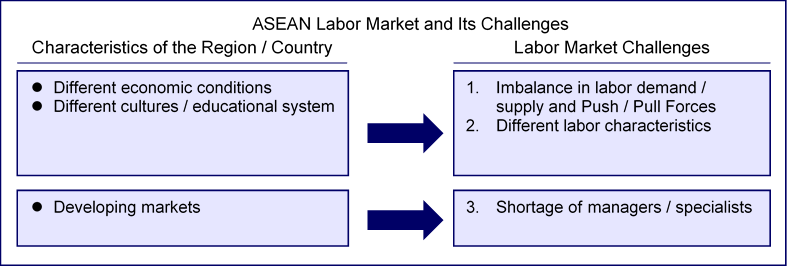

- There is an imbalance in labor supply and demand due to differences in economic conditions and educational systems between ASEAN countries. As a result, Push and Pull Forces have emerged that stimulates the flow of labor between the countries. At the same time, there is a shortage of managers and specialists in developing markets.

- There has been much effort towards AEC but the moment, the “free flow of labor” principle is not universal; rather it is only applicable to a limited labor pool.

- It is important for businesses to monitor the ASEAN labor market and the development of the AEC and improve competitiveness through the optimization of managers, specialists and workers.

※In this report, we abbreviate the name of ASEAN countries as follows and sort them by monthly income in bar graphs. SI: Singapore, BR: Brunei, MA: Malaysia, TH: Thailand, PH: Philippines, VI: Vietnam, IN: Indonesia, CA: Cambodia, LA: Laos, MY: Myanmar

I. ASEAN Labor Market

1. Labor Demand-Supply Imbalance

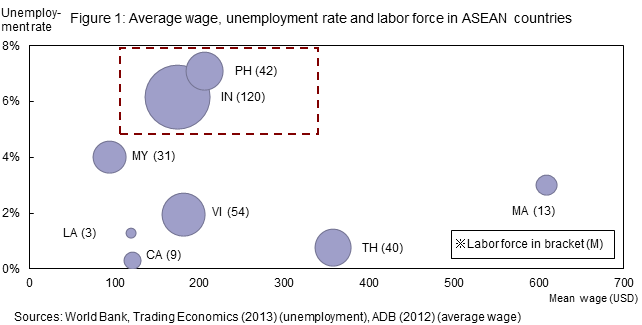

Due to different economic conditions among ASEAN countries, workers often move from countries with low standards of living to countries with higher ones in search of higher income. It is very common to have Cambodians in Singapore’s construction industry or Vietnamese in Thai restaurants. Figure 1 shows the average wage, unemployment rate and labor force of ASEAN. We see that Indonesia and Philippines have a large labor force and are currently facing high unemployment and low income. For these reasons, there is a tendency for labor to flow from these countries to neighboring ones (Push Force).

On the other hand, Thailand and Malaysia have high living standards and low unemployment rates, which attract labor from the remaining six countries (Pull Force).

2. Labor Characteristics

There are also various ways to evaluate the “quality of labor” in each country. In this report we would like to highlight a few of them.

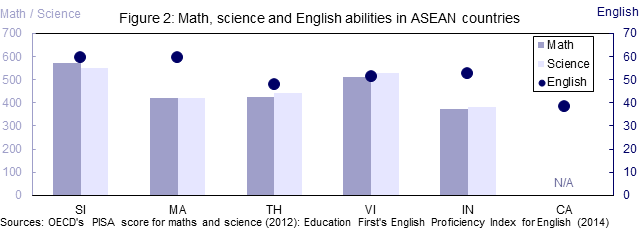

For example, if we look at math, science and English test scores (Figure 2), there appears to be no correlation between them and economic standards. Rather, these scores reflect the educational system and cultures of the concerned countries.

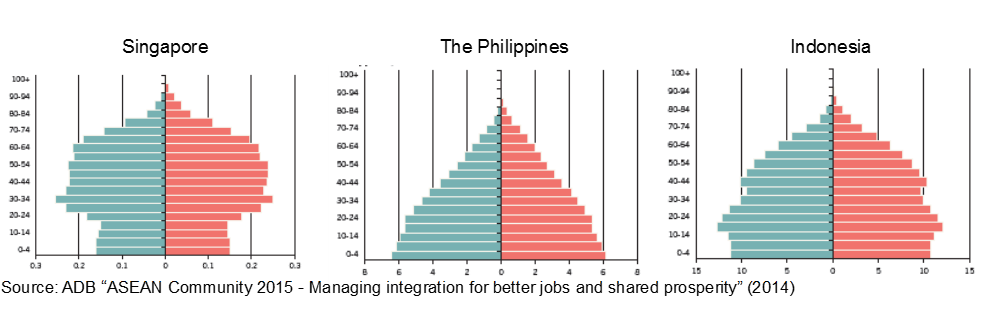

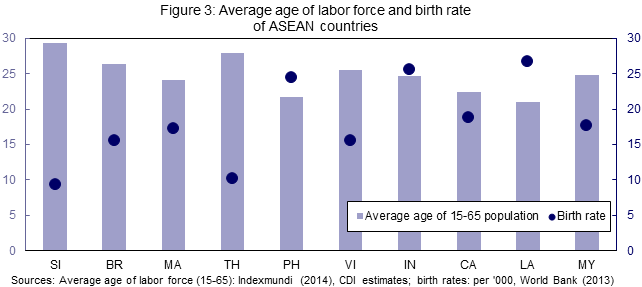

Furthermore, by looking at the age of the labor pool in each country (Figure 3), we see that the populations of the Philippines and Laos are relatively young. As such, it is believed that there will be a great dispersion among the population structures of each country in the future (Figure 4). This will be another factor stimulating the movement of labor within ASEAN.

Figure 4: Population pyramids (2025)

3. Shortage of Managers and Specialists

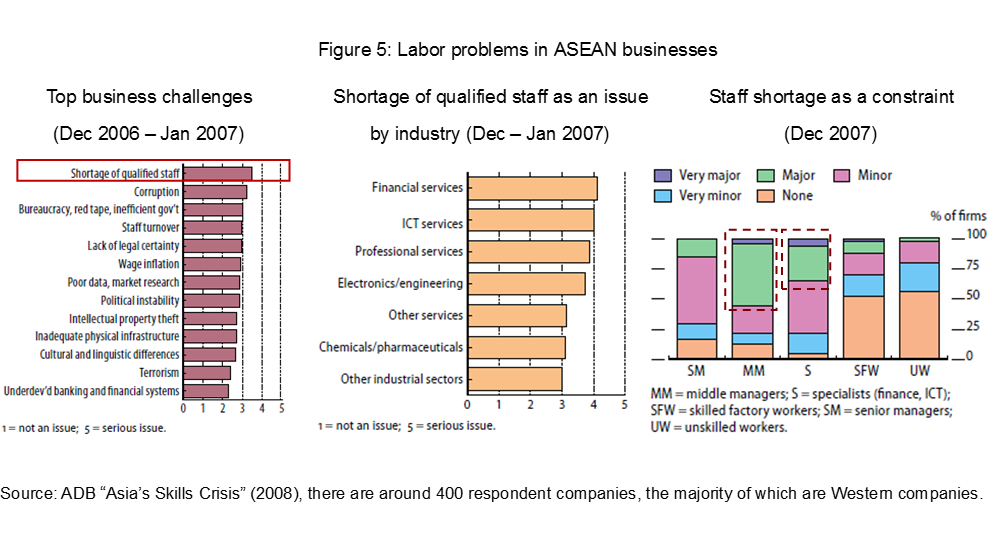

Although the data is a bit old, according to International Labor Organization (ILO)’s ASEAN business survey (Figure 5), the largest concern for ASEAN businesses is the shortage of skilled labor. Looking across industries, it appears that this problem is most serious in finance, ICT and other professional services. Furthermore, looking across professional layers we find that middle managers and specialists are the most in demand.Shortage of Managers and Specialists

II. ASEAN Labor Policies

What has ASEAN nations done to overcome the above challenges?

While AEC aims at “facilitating the free flow of goods, services, investments, and labor, thereby creating a single market place”, at the moment the free flow of “labor” is not a universal principle; rather it is only applicable to certain labor pool.

1. ASEAN’s Progress in Establishing the Free Flow of Labor

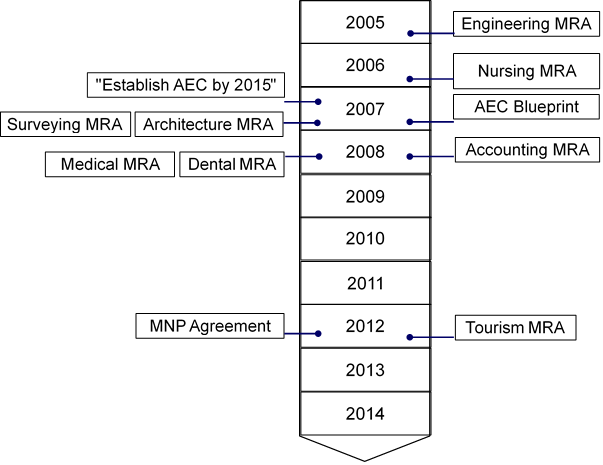

Figure 6: History of liberalization of labor flow within AEC framework

According to the AEC Blueprint signed in 2007, ASEAN will “facilitate the issuance of visas and employment passes for ASEAN professionals and skilled labor who are engaged in cross-border trade and investment activities”, particularly in the four priority sectors (air transport, e-ASEAN, healthcare and tourism) as well as the logistics industry. In order to accomplish this goal, the authorities have gone as far as to recognize each other’s educational and professional qualifications and award the “ASEAN professional” designation through the creation of the ASEAN common curriculum and certification system. In particular, the ten ASEAN countries began to sign MRAs (Mutual Recognition Agreements) by which such ASEAN professionals would be allowed to seek employment anywhere within ASEAN. In 2005, the Engineering MRA was the first one to be signed, followed by Nursing, Surveying, Architectural, Medical, Dental, Accounting and Tourism MRAs. In total, 8 professional designations have been established. As a result, individuals who would like to seek employment overseas may obtain the “Professional” designation through the MRA system and proceed to apply for the work visa.

In addition, the MNP (Movement of Natural Persons) Agreement was signed in 2012. Through this agreement, foreign travelers who would like to enter a country to conduct work related to his/her current employment may be able to obtain the work visa upon fulfilling certain conditions.

Although there has been progress in the region as a whole, in reality it is not easy to apply the complex frameworks and national laws have not been updated, limiting the actual implementation of the system.

a. MRA (Mutual Recognition Arrangement)

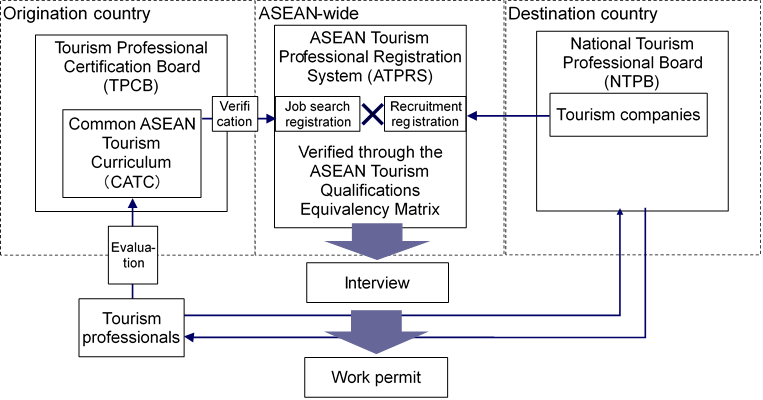

Figure 7: Tourism MRA’s “Professional” approval system

Source: ASEAN, “Mutual Recognition Arrangement on Tourism Professionals (MRA) – Handbook”, 2013

According to this system, if a tourist worker wishes to work in the destination country, he/she would first get certified as an ASEAN tourism professional through the Tourism Professional Certification Board (TPCB). Subsequently, he/she would register his job-search status on the ASEAN-wide ATPRS and be matched with a recruiting company. After being interviewed, the individual be issued a work permit for the destination country.

Although this framework is expected to bring about labor flow liberalization, there are some problems with its execution.

- The candidate must be a “professional”, hence the target labor pool is limited.

- With the tourism MRA for example, tourism professionals are classified into certain categories. The TPCB will then rely on the CATC to determine whether the individual possess the required skills for the corresponding category.

※In the case of the stricter Engineering MRA, the individual is required to graduate from an engineering university of the origination country, have over 7 years of experience, and collaborate with local engineers.

- Even after receiving the appropriate professional designation, the destination country can decide whether to issue the work visa or not based on its own laws and regulations.

- Although ASEAN countries have agreed to follow these agreements to liberalize labor movement, they are not obliged to make the appropriate legal reforms. In fact countries are free to make these reforms at the own pace. Such legal obstacles include:

- Constitutional provisions prohibiting the employment of foreigners in certain industries

- Upper limit on the number of foreign employees (Malaysia)

- Economic market / labor market tests (EMT/LMT)

- Requirement to hire a replacement local employee at the end of the work duration of the foreigner (Indonesia, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar)

- Although ASEAN countries have agreed to follow these agreements to liberalize labor movement, they are not obliged to make the appropriate legal reforms. In fact countries are free to make these reforms at the own pace. Such legal obstacles include:

- Even when the individual satisfies all conditions, the procedures to get the visa may be costly or take a long time. The procedures themselves are known to be non-transparent.

- The supporting databases (ATPRS, ATQEM) and organizations (TPCP, NTPB), etc. are all public entities. As such, they are slow to respond to market changes and can only progress when there is collaboration among the ASEAN countries.

b. MNP (Movement of Natural Persons)

MNP is an agreement that promises the issuance of visa for ASEAN personnel who are managers or specialists seeking entry into a country as required by their current job. Note that MNP is not applicable for unskilled labor or generalists. Nonetheless, MNP is expected to have a greater impact than MRA.

This agreement covers 154 service sectors and three travel types: (1) business trip (sales, business negotiations, investment preparations, etc.), intra-corporate transferee, (3) contractual service suppliers.

For your information, we have outlined the commitment of each country below (Figure 8). You can also look up the sectors covered under the “MNP Schedule” of each country at the following link:

http://www.asean.org/communities/asean-economic-community/category/agreements-declarations-12

Figure 8: MNP commitments

Source: Fukunaga & Ishido, “Values and Limitations of the ASEAN Agreement on the Movement of Natural Persons” (2015)

Currently, these commitments are solely within the AEC framework. Similar to the MRA situation, the countries have not yet made legal / regulatory reforms which at the moment are not compulsory.

2. Individual Countries’ Efforts

As highlighted above, since the ASEAN system is inflexible and the covered labor pool is limited, such system is not expected to impact the labor movement to a great extent. On the other hand, each country may proceed to relax their policies based on their own labor market situation. One example is Thailand where there has been an increasing problem of illegal Vietnamese workers. There has been a new regulation according to which for a period of 30 days since 1 Dec 2015, Vietnamese illegal workers can register and receive working permits. These individual national efforts are also expected to facilitate the establishment of a single ASEAN labor market.

III. Strategic Implications for Businesses

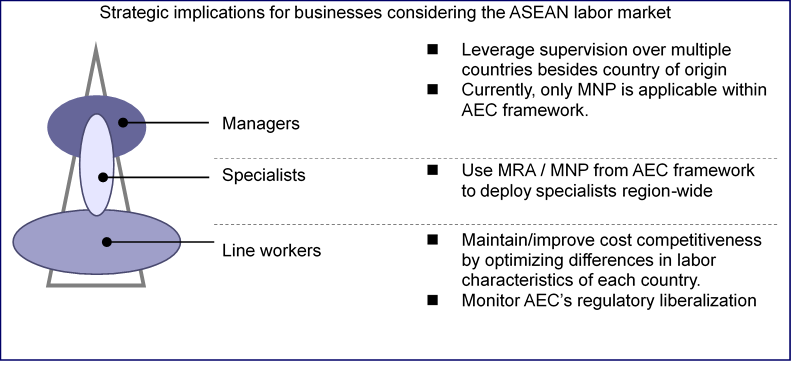

At this point, we will summarize the implications for businesses in ASEAN based on the challenges and regulatory changes analyzed thus far.

At the manager level, it is advantageous to let one person supervise multiple countries given manager scarcity in the region. In other words, companies must set the appropriate management scope, remuneration and training for the “ASEAN regional talent”. For such occasion, we recommend the use of the MNP for its temporary work-related stay provisions. In particular, the upper management layer has more potential for regionalization given lower national interests to protect equivalent local employees compared to the middle management layer.

With regards to specialists, they can expect to move more freely as the AEC further develop. Businesses can therefore make use of specialists to provide products and services to their markets at a consistently high quality, thereby improving competitiveness. In particular, as MRA / MNP mechanisms further improve, businesses can actively deploy regional talents to manage the demand-supply imbalance.

As for line workers, businesses must maintain cost advantage by leveraging low costs and other labor characteristics of each country. It is also important to continue monitoring regulatory liberalization within the AEC process to catch opportunities should they arise.

CDI Asia Business Unit Consultant, PHAM Le Duc

CDI Asia Business Unit Director OGAWA Tatsuhiro

December 2015

Download attachments

Download attachments